In the early 16th century, the city of Florence found itself at the crossroads of artistic genius. The Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio, an imposing chamber that already echoed with civic pride, became the stage for a remarkable artistic duel. The city commissioned two of its most celebrated artists to adorn opposing walls with frescoes depicting pivotal battles from Florence’s history. On one side, Leonardo da Vinci was to paint the Battle of Anghiari. On the other, a young Michelangelo Buonarroti was assigned the Battle of Cascina.

The contrast between these two masters couldn’t have been starker. Leonardo, ever the meticulous scientist, envisioned a scene teeming with chaos and dynamism: knights and horses locked in a ferocious struggle. His preparatory sketches reveal a masterclass in movement, tension, and raw human emotion.

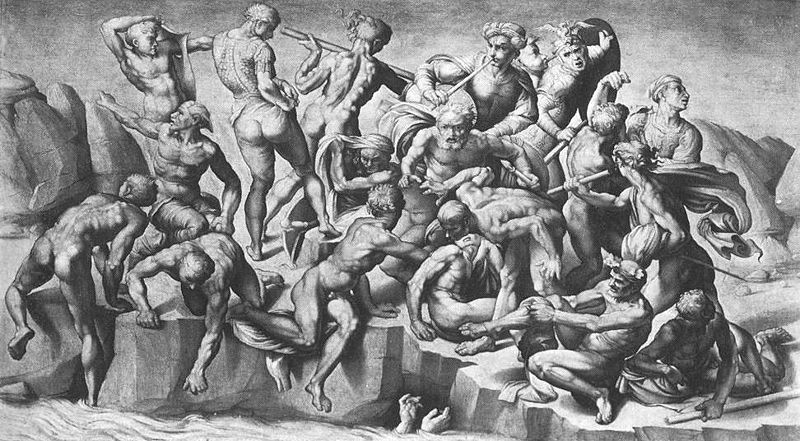

Michelangelo, however, took a different path. His surviving sketches show—not the battlefield—but a group of naked men bathing in a river. Yes, bathing. At first glance, it’s a perplexing choice. What do these well-formed, unclothed figures have to do with the Battle of Cascina? The answer lies in the backstory of the conflict. According to contemporary accounts, the Florentine soldiers were caught off guard while cooling off in the river. The Pisans launched a surprise attack, forcing the Florentines to hastily don their uniforms and rally to victory. It was a moment of vulnerability transformed into triumph, and Michelangelo zeroed in on the vulnerability.

But was this really about storytelling? Or was it, as some suspect, another example of Michelangelo’s lifelong fascination with the male form? From the towering David to the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling and altar wall, Michelangelo’s art is a testament to his obsession with anatomy. His work on the Palazzo Vecchio fresco—though never completed—can be seen as part of this thematic throughline. The Battle of Cascina wasn’t so much a depiction of military glory as it was an opportunity to explore the human body in all its complexity.

This subversion of expectation is quintessential Michelangelo. While Leonardo dissected cadavers to understand the mechanics of movement, Michelangelo’s figures seemed to burst forth from his imagination fully formed, their musculature both idealized and deeply human. He managed to “smuggle” these studies of the nude into some of the most public and sacred spaces of his time. Consider the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel: from the Creation of Adam on the ceiling to the apocalyptic tableau of The Last Judgment on the altar wall, Michelangelo populated these works with a veritable parade of unclothed figures. It’s almost as if he turned every commission—no matter the subject—into an excuse to celebrate the human form.

And yet, there’s a brilliance to this audacity. Michelangelo didn’t just sneak these images past censors; he elevated them to the realm of the divine. By placing the nude at the center of his artistic universe, he challenged viewers to confront their own perceptions of beauty, vulnerability, and power. In the case of the Palazzo Vecchio, he took a moment of historical humiliation—Florentine soldiers scrambling out of the water—and transformed it into a timeless meditation on the body and its resilience.

Even today, Michelangelo’s unfinished Battle of Cascina sketches provoke as much curiosity as awe. They remind us that art’s greatest power often lies in its ability to reinterpret and reframe the world. For Michelangelo, battles weren’t just fought with swords; they were waged on the canvas, in the interplay of light, shadow, and form, where the human body became the ultimate battlefield.

In the 21st century, artists continue to grapple with the tension between personal vision and public expectation. Commissioned works often come with constraints, whether from institutions, patrons, or the marketplace. Yet, much like Michelangelo, contemporary artists find ways to inject their voice into the framework of a brief. Consider how modern muralists use public art to tackle social issues or how digital artists reclaim virtual spaces to challenge norms. The act of creation remains a delicate negotiation—an interplay of compliance and rebellion. Today’s artists also face a democratized but competitive landscape, where algorithms and social media platforms act as both gallery and gatekeeper. The challenge is no longer just about convincing a patron but about breaking through the noise to connect with an audience. Michelangelo’s defiant reinterpretation of a commission reminds us that great art often emerges not in spite of constraints but because of them. It’s a lesson in the enduring power of vision and audacity, one that resonates as strongly now as it did in Renaissance Florence.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

Leave a comment