For most people, the morning is a ritual of familiarity. My grandfather used to read the newspaper while the radio droned the morning news, offering him a constant stream of updates to critique over breakfast. My mother, more focused, restricts herself to the local news—traffic, weather, maybe a fire or two. My wife, in contrast, scrolls through real estate listings, dream homes nestled among the mundane. As for me, my mornings revolve around potential.

I check open calls for art submissions. Like a stockbroker hunting for market opportunities, I sift through galleries, competitions, and grants, noting deadlines and requirements. If something aligns with my body of work, I log it in my database. Then, the process begins: selecting the artwork, fine-tuning the photos, updating my artist statement, and compiling my CV. Most applications take an hour at most. But occasionally, there’s a twist—a request for more than the usual documentation.

“Tell us the story behind the piece,” they say.

At first glance, it’s an unnecessary ask. Isn’t the art enough? But then I remember what a gallerist once told me: People don’t buy art. They buy stories.

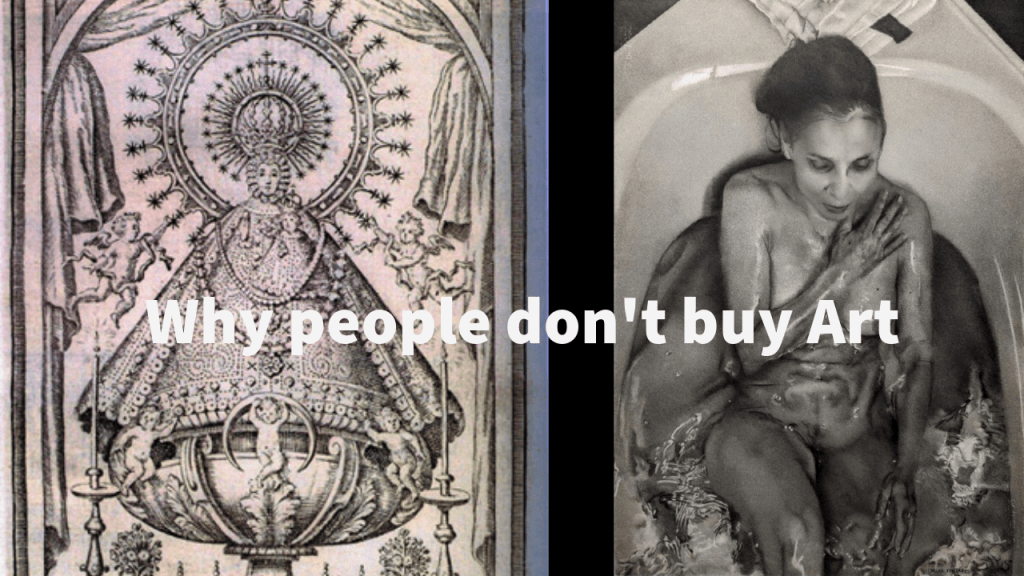

Take my latest drawing, True Effigy of Our Lady of the Fishes According to How I Remember Her When She Came In Through the Bathroom Window. The title alone feels like a story waiting to be told, doesn’t it? And yet, the story behind it is as much about process as it is about inspiration.

It started with a crossroads. After completing a previous work, Self Isolation or the Unsung Story of How Dreams Unconsciously Interfered with My Daily Life, I found myself questioning my direction. That piece had been a finalist in the 16th ARC Salon and featured in their catalogue—a milestone for me. But success breeds its own kind of uncertainty. What comes next?

I decided I wanted to create another portrait, but this time with a vertical composition—something that felt more narrative, more intimate. And I knew it would be a nude, though not the kind of airbrushed perfection that dominates galleries. No, I wanted something raw, unvarnished, and deeply human.

The setting revealed itself almost serendipitously: a bathtub. Think about it—a space that straddles the line between private and universal. Vulnerable yet reflective. The works of Lee Price and Sara Gallagher, with their meditative depictions of women in water, influenced my thinking.

From there, the piece unfolded like a conversation. Each stroke of the pen felt like a revelation. The koi fish swirling around the figure became both literal and symbolic, adding layers of meaning and movement. The title, too, emerged organically, inspired by a mashup of childhood memories, religious iconography, and a surreal sense of narrative.

But there’s more. There’s always more.

The composition owes a debt to the Spanish and colonial paintings of Saint Mary that I grew up admiring. I even inherited one—a relic my great-grandfather brought from Spain to Mexico in the early 20th century. In those works, Mary is often cloaked in wide robes, surrounded by cherubs. In my drawing, water replaces the robe, koi fish replace the cherubs, yet the essence remains: a central figure surrounded by a constellation of symbols.

This is the kind of composition that feels timeless, almost archetypal. Whether you’re looking at a Murillo or a Bacon, a Picasso or a Chuck Close, the structure persists: a main figure flanked by a supporting cast of meaning. It’s deceptively simple, yet endlessly versatile.

For me, Our Lady of the Fishes became more than just a drawing. It’s an exploration of vulnerability, of beauty found in imperfection. It’s a dialogue between the classical and the contemporary, memory and imagination, realism and surrealism.

And perhaps that’s the real story behind submitting art. It’s not just about meeting deadlines or perfecting applications. It’s about putting your voice into the world and hoping it resonates with someone who sees not just the work, but the story within.

Leave a comment