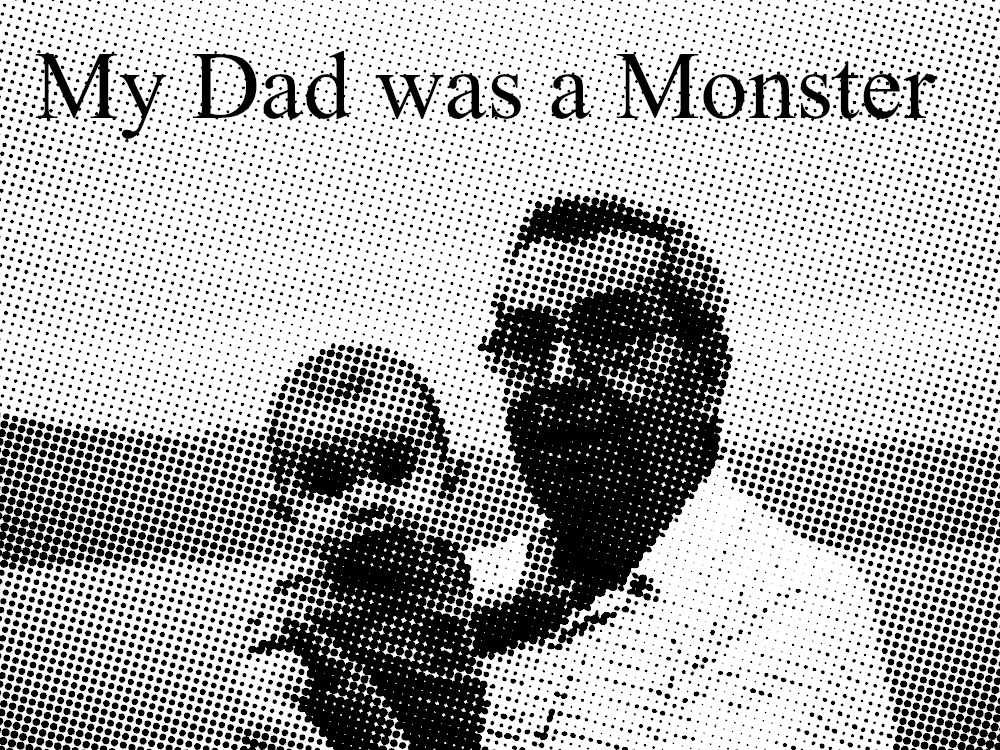

On Christmas Day 2024, my father passed away at the age of 85. He was, in the truest sense of the word, a monster—but not the kind that lurks in shadows with fangs and claws. He was the kind only a father can be: imposing, untouchable, a presence that overshadowed everything around him. And I loved him deeply.

He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in his late 60s, a revelation that reshaped the trajectory of our relationship in ways I’m only beginning to understand. My father wasn’t a man of tenderness or gentle words. He wasn’t one to discuss politics, art, or even sports. In many ways, he existed in the world as a force of certainty—one that never once explained what he truly believed. And when it came to my art? That, too, was part of the unspoken void between us.

My father never commented on my work, neither to praise nor to criticize. It was as if art itself was something beyond his comprehension, an abstract concept he couldn’t grasp. This absence of opinion, though, felt like rejection. He never attended any of my shows, not because he didn’t care, but because, in his mind, art had no place in the world. It was an indulgence, a frivolity. His world was one of pragmatism, a world where securing a stable job, preferably in something “useful,” was the primary goal. Accounting, engineering, business—these were the domains he valued. Art? It didn’t fit into that equation.

At 18, I wanted nothing more than to attend art school. The idea consumed me. But my father stood firm. “You need to study something useful first,” he told me, with my mother backing him up. It was devastating, a moment that left me feeling adrift. What was I supposed to do with my life if the thing I loved most was considered a distraction?

But “useful,” to me, was an abstract concept. My older brother had chosen accounting, and occasionally, I’d help him with his work. I soon learned that the world of numbers was one of strict precision. Errors were unacceptable. Everything had to add up. It was a world devoid of ambiguity, and I knew, deep down, that it wasn’t for me.

Instead, I enrolled in architecture—a compromise, a bridge between my passions and my father’s expectations. But before I committed fully, I visited the Fine Arts faculty at the university. I had imagined it as a sanctuary for creativity. What I found, instead, was a relic of something that no longer existed. The building was dark, neglected, and eerily silent. The murals on the walls—remnants of Mexico’s muralist movement—felt like ghosts of a time long past. Lenin, Marx, the hammer and sickle, frozen in time. It was less a place for creative expression and more a monument to a bygone ideology. I left that day with no doubt that my path lay elsewhere.

My father’s bipolar diagnosis came late, and with it, a prescription for medication to stabilize his moods. The drugs worked—too well, in a way. They tempered his anger, his volatility, but they also muted the vibrancy that had once defined him. I remember the man he had been before—always restless, always searching for something new, whether it was a product innovation or the latest technology in his field. After the medication, that drive seemed to evaporate. He was flat. Dull. A shell of the person he had once been. The question that haunted me was this: Did I want him back—the father with all his flaws, his anger, and unpredictability—or the medicated version, the more subdued version of himself? And in some ways, it made me wonder about my own mind. What if I, too, was diagnosed with something similar? Would I take the red pill and stay in Wonderland, knowing full well the consequences?

There’s a deeper irony here, one I’ve been turning over in my mind for years. We live in a world that values normalcy, consistency, and the reproducibility of outcomes. Science, with its formulas and equations, offers a path to certainty. Art, on the other hand, resists this logic. It cannot be measured, replicated, or reduced to a formula. Take Glenn Gould’s two recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations—two renditions, separated by decades, and yet each is completely unique. Or Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon—no replica can ever truly capture its essence. Art exists outside the realm of certainty, which, in many ways, makes it an uncomfortable concept for people like my father.

And yet, we are captivated by it. It’s a paradox that’s impossible to fully resolve. My father never understood it, and perhaps that’s why I wrestle with it so much. It’s a world that cannot be explained in clear-cut terms, a world that forces us to confront the ambiguity and imperfection of our existence. Art, much like my father, defies easy categorization. It is at once frustrating, beautiful, and incomprehensible—but perhaps that’s what makes it so compelling.

Leave a comment