“When are you gonna come down?

When are you going to land?”

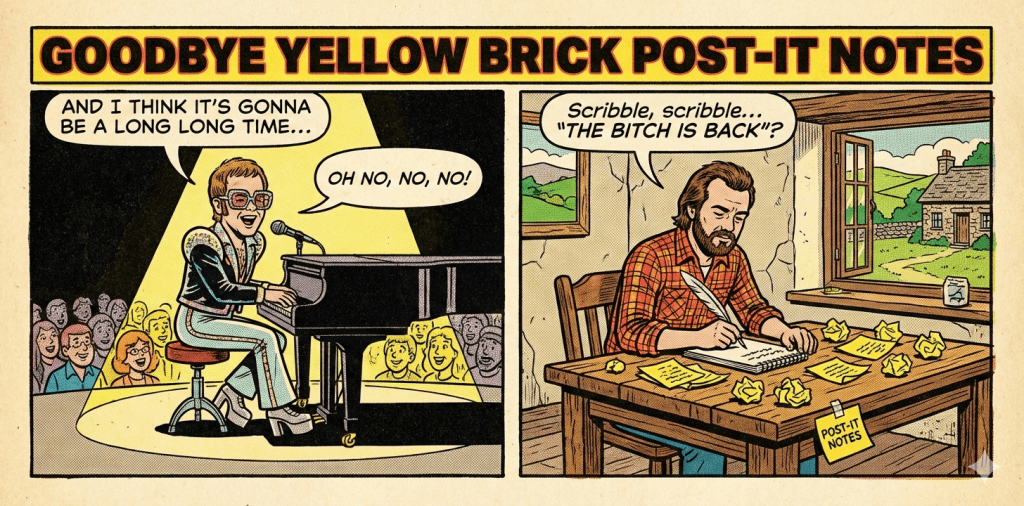

“Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” is usually understood as a song about disillusionment with fame. That interpretation is not wrong. It is just incomplete.

Across decades of interviews, Elton John has framed the song as hypothetical rather than confessional: a character who tastes success and finds it hollow. Elton insists it was never autobiographical. He did not intend to abandon fame. He did not, in fact, abandon fame. In this telling, the song becomes a thought experiment—a parable about glamour rather than a diary entry.

But that explanation quietly sidesteps an inconvenient fact: Elton John did not write the lyrics.

Bernie Taupin did.

And in the early 1970s—precisely when Goodbye Yellow Brick Road was written—Taupin did something that sounds uncannily like the song itself. He bought a farm in rural Lincolnshire, the region where he had grown up. He returned, quite literally, to his plough.

That detail matters.

Because when we reread the lyrics with Bernie Taupin—not Elton John—as the emotional center of gravity, the song begins to look less like a philosophical abstraction and more like a personal statement disguised as fiction.

“You know you can’t hold me forever.

I didn’t sign up with you.

I’m not a present for your friends to open.”

Those lines do not sound like a meditation on fame in general. They sound like a boundary being drawn.

Taupin and John were already a famous duo by then, but their relationship was asymmetrical. Elton was the public body—onstage, photographed, consumed. Bernie was the invisible engine, the private writer. Their partnership was essential, but it was not evenly illuminated. And while Elton was leaning into spectacle, Taupin was leaning away from it.

In that context, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road starts to resemble something else entirely: an internal communication. Not a confrontation. Not a resignation letter. Something subtler. A message embedded where confrontation could safely occur—inside the work itself.

This is where the song becomes interesting not as biography, but as a case study in creative collaboration.

We tend to imagine collaboration as alignment: two minds moving in the same direction, toward the same ambition. But in reality, the most durable collaborations are often negotiations. One partner accelerates. The other resists. One wants the spotlight. The other wants distance. And the friction between those impulses does not always get resolved in conversation. Sometimes it gets resolved in art.

“I should have stayed on the farm.

I should have listened to my old man.”

That line lands differently when you know Taupin actually did stay on the farm. It stops being metaphorical. It becomes retrospective. Almost declarative.

Of course, there is no documentary evidence that Taupin wrote the song for Elton in this way. No letter. No interview confession. No smoking gun. But that absence may be the point. Creative partnerships—especially successful ones—rarely survive blunt honesty. Direct confrontation threatens the engine itself. So messages get rerouted. They surface as tone, as imagery, as narrative voice.

Art becomes a safe medium for unsafe truths.

Seen this way, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road functions less like a hit single and more like a memo written in melody. Not an ultimatum, but a clarification: this is as far as I go. I will write the songs. I will help build the world. But I will not live in your penthouse. I will not be ornamental. I will not be opened and displayed.

“You can’t plant me in your penthouse.

I’m going back to my plough.”

What makes this interpretation compelling is not that it can be proven, but that it explains something otherwise puzzling: how two people with radically different appetites for fame managed to collaborate so productively for so long. Taupin did not have to abandon the partnership to protect himself. He could redraw its emotional boundaries from inside the work.

This suggests a broader insight about creative processes. We often ask: Is it better to address conflict directly? But creative history suggests another option. Sometimes the most effective way to communicate tension is not through conversation at all, but through contribution.

The work becomes the site of negotiation.

That does not mean every song is a coded argument, or every novel a veiled complaint. But it does mean that creative output can function as a parallel communication channel—one that allows collaborators to say things they cannot afford to say out loud.

In that sense, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is not just a song about rejecting fame. It is a demonstration of how collaboration survives difference. One partner runs toward the lights. The other writes a song about leaving them. And somehow, remarkably, the machine keeps working.

Even if there is no evidence that this is true. Sometimes coherence is not proof—but it is a clue.

Leave a comment