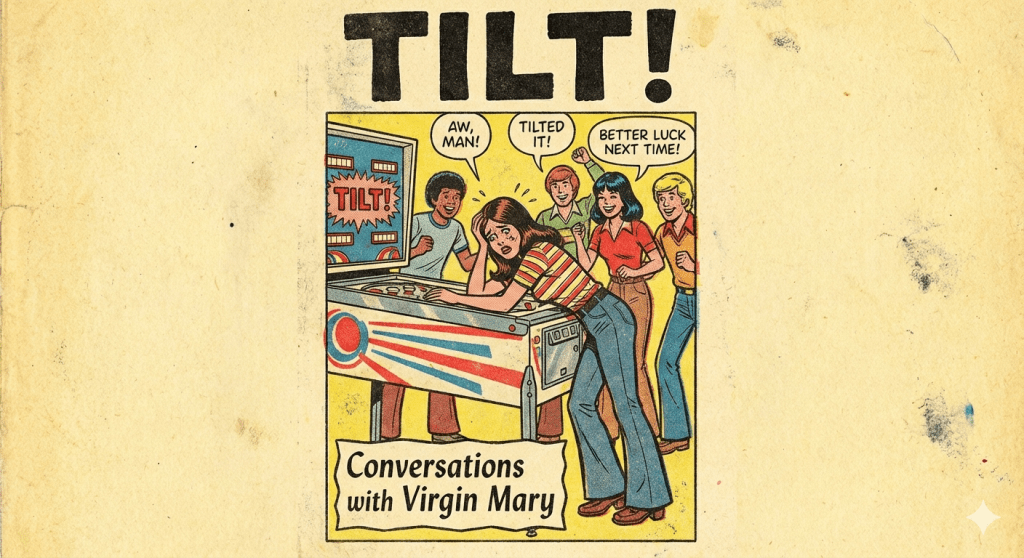

Conversations with Virgin Mary

Saturday May 29

“Oh no. Tilt.”

The word flashes in red, and the ball goes limp—flippers locked, momentum gone. A moment earlier you thought you had the angle, the timing, the control. But the machine decided otherwise; one nudge too far, and everything you’d built—points, progress, the fragile sense of mastery—vanished with the ball slipping into the drain.

When you tilt, you don’t just lose the ball. You lose everything—the progress, the rhythm, the fragile sense you knew what you were doing. The machine wipes you clean and dares you to begin again.

That’s the part players forget. Pinball isn’t about outsmarting the system. It’s about staying in play. It’s about knowing when to act, when to wait, when to trust momentum, and when to intervene. You keep the ball alive; the points take care of themselves.

But we like shortcuts. We like to imagine we can beat the machine by force of will, by cleverness, by a quick nudge when no one is looking. We forget the machine doesn’t care. It doesn’t get angry; it doesn’t negotiate. It simply enforces the rules written into its wiring. Push too hard, and it tilts. Every time.

You sigh. You restart. You promise to play differently.

I’ve been watching you play this game longer than you remember. Here’s what I see: It’s not about beating the machine—no one beats the machine—but to move through it with purpose. To build your score one point at a time. To keep the ball alive.

Stop cheating. Stop rushing. Stop thinking the machine owes you anything. The rules aren’t your enemy. They’re the map.

You look at the darkened playfield, at the empty trough waiting to load the next ball.

So tell me—what message do you want to see at the end of all this?

Tilt?

Or ‘Please enter your initials’?

During the pandemic, I joined a Facebook group dedicated to hyperrealism. It was organized by David Wilson, then CEO of the Ibex Collection. My intention was simple: to improve my technique. The group was international—artists from Vietnam, the Netherlands, the United States, Mexico—working at radically different skill levels, but bound by the same obsession with detail, surface, and patience. It became one of the things that kept me anchored during lockdown.

I learned a great deal, but more importantly, we learned from each other. That sense of shared discovery mattered. Eventually, we decided to formalize the group. With David’s help, we moved to Discord. He was generous with his time, structured in his thinking, clearly shaped by years of teaching. The artists responded to that. We named the group DNA3: Decentralized Network of Artists. The “3” stood for Web3. It was the height of the NFT moment.

Everyone wanted to mint something.

To me, it felt absurd. Selling a JPEG for sums that sometimes exceeded the value of the original work struck me as speculation masquerading as revolution. I didn’t hide my skepticism; I voiced it openly in the group. At the time, I felt out of sync with everyone else. Now, looking back, I realize my unease wasn’t misplaced.

Not long after, David disappeared. He left Ibex, started his own venture, and without him the gravity shifted. One by one, the artists drifted away. The energy thinned. The experiment dissolved quietly, without drama.

Recently, I spoke with two of the original members. At the beginning, there were only five of us. They’re both busy now, but not exactly making art. One runs a software development firm. The other works with people suffering from mental disorders, particularly those struggling with suicidal ideation. He is himself a survivor.

I was glad to talk to them. It felt like returning to an old arcade—nostalgic, slightly sad, but warm. At first, everyone wants to play the brand-new pinball machine, the one with the flashing lights and the long line behind it. But after a while, each person gravitates toward the table they love most. Indiana Jones. Star Trek. Kiss. And each of us, in our own way, is just trying to keep the ball in play as long as possible.

I was explaining Jorge about how I entered in the figurative art world, I stared at the cup in my hands, filled with a deep blue-purple infusion.

“What did you say this was called?” I asked. “Butterfly pee?”

“Butterfly Pea Tea,” he said, smiling. “A friend brought it from Thailand.”

His hands trembled slightly as he held the cup. After spending many afternoons with him, I had learned to recognize his Parkinson’s—not dramatic, but unmistakable once you know his movements.

“You understand perfectly,” he continued, as if we had never changed subjects. “It’s not that they quit. They just changed tables. You’re looking at the same events from a different angle now. And I think it’s time I tell you how I tamed my Parkinson’s.”

He spoke slowly, deliberately, as if waiting for me to be old enough to hear it. By old enough, I realized that I finally knew his story.

“My recovery started when I gave up control. I followed the flow. I changed my mindset.”

“Mindset is the hardest part,” he continued. “Once you get there, the road becomes lighter. Less twisted.”

“This isn’t about obsessing over the disease or repeating mantras like My health is perfect. It’s about staying in the zone. Balancing your life. Forgetting the problem enough to keep moving. Like the ball in the pinball table—you don’t tilt the ball, you keep it playing. Once the ball is out, your job is to keep it there as long as you can. When I got the diagnosis, I have two options to fight or to quit but the ball was already out and playing. I chose to fight.”

I looked at him with a half-smile, unconvinced.

“I’ve read all those self-help books,” I said. “They promise abundance, health, love. Same formula every time: write what you want, align your mind, feel the vibration, and it’s done. And when nothing happens, the answer is always the same—you didn’t believe enough.”

I paused, then added, “Did you know Napoleon Hill, the author of Think and Grow Rich, died in debt? And he’s the blueprint for every new-age guru. So now you’re telling me the answer is still there?”

He didn’t argue.

I took a sip of the tea.

“Yes,” he said, “the so-called Law of Attraction—overused, misunderstood, just like quantum mechanics. There are charlatans everywhere. I know that. What I’m telling you isn’t magic. It’s this: there’s more going on than what we can fully explain. I don’t know how it works—but I know it works.”

“You already suspect this,” he said. “But you don’t want to accept it yet. Once I understood what these teachings were actually proposing, I didn’t quit. I stayed in the game. I played by the rules. I didn’t cheat.”

His eyes fixed on the wall, as if searching for the right words.

“The game isn’t over until it’s over,” he said. “No one can stop you before that. People can tell you there’s no hope—doctors, specialists, partners, judges—but none of them decide when your game ends. You do.”

“These letters helped me stay in the game. They taught me to clean my house. To change my environment. To throw away rotten food from the fridge. Those things kept my ball in play. But it was my game. I can’t play yours. I can only show you what I did. I don’t know if it was belief changing my body, or belief changing my choices. Probably both. But I know this: once I stopped fighting the diagnosis and started working with it, my symptoms improved.”

“You’ll hear many voices telling you to quit. To leave the table. To accept that the game is impossible. But it’s not their game. You always have the last word.”

He paused, then added quietly:

“Your art, your submissions, your father, your doubts—nobody can play your game for you. Your hands are on the controls. And it’s the same with your mother’s illness. That isn’t in your hands. It’s in hers.”

“All you can do,” he said, “is change your mindset… and keep the ball in play.”

After that, he handed me a booklet.

Its title read: Health Impacts of Diesel Exhaust: Supporting Evidence for Public Health Warning Legislation.

“This is my next move,” he said. “My way of saving democracy. I gathered the information, organized it clearly, and now I have a written proposal ready to be voted on in Parliament. If you want to stay in the game, you have to play inside the game. I learned that from Hamilton.”

I looked at the booklet, then back at him.

How does Jorge find the energy to write an entire policy proposal on diesel exhaust while I collapse at the first rejection letter?

I looked at the booklet again. Health Impacts of Diesel Exhaust. Evidence. Citations. A proposal ready for Parliament.

The answer was in the pinball letter: he stayed in play. He didn’t tilt when doctors said there was no cure. He didn’t walk away when his sister blamed him for everything. He just kept the ball alive, one point at a time.

And now he was asking me: What message did I want to see at the end? Tilt? Or my initials on the board?

Leave a comment