Conversations with Virgin Mary

Monday, October 5

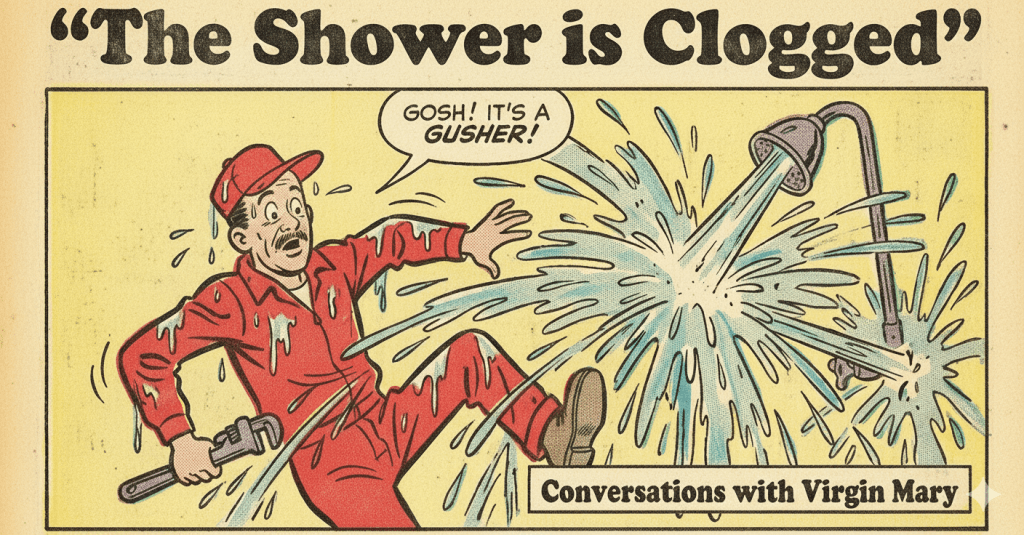

Imagine this. You check into a luxury hotel. You are tired. You decide to take a shower.

The bathroom is immaculate—neat, spacious, state-of-the-art. You turn the knob.

Instead of a soft, predictable stream, water shoots out in all directions. Thin, noisy jets ricochet unpredictably. There is water everywhere except where it should be.

You understand immediately what has happened: the shower is clogged.

A showerhead is not a complicated object. Its job is simple. It exists to let water pass through it. It takes a pressurized stream of water and breaks it into multiple smaller jets. That design increases surface coverage while reducing force, making the water comfortable rather than damaging. The small openings regulate pressure, conserve water, and create a predictable pattern of flow.

In other words, the showerhead is a mediator. It turns raw pressure into something usable.

But here is the catch. That very design—the tiny openings that make the shower pleasant—also makes clogging inevitable.

There is no perfect showerhead. Its failure does not depend on poor engineering; it depends on the water itself. How heavy it is. How many minerals it carries. With every use, tiny residues are left behind. Calcium accumulates slowly, invisibly. The showerhead continues to function in principle, but its efficiency degrades because the conditions it was designed for no longer exist.

You know what this looks like. Pressure drops. The spray pattern becomes capricious. The flow is erratic. The shower technically works, but it is frustrating and inefficient.

So what do you do?

You do not increase the water pressure. That only makes things worse.

You either clean the showerhead—or you replace it.

This is where the analogy becomes uncomfortable.

Because we function in much the same way.

You are a state-of-the-art mechanism. You are designed to perform under pressure. Under pressure, your senses sharpen. Your reactions quicken. Decisions are made faster. Pressure, up to a point, is not harmful. It is productive.

But pressure sustained over time produces accumulation. Just like minerals in a showerhead, unresolved stress, unresolved emotion, unresolved loss begins to build up. You still function. You still show up. But your efficiency degrades. Your flow becomes erratic.

You clog.

At that point, the diagnosis is the same: cleaning or replacement.

Most of us choose the equivalent of turning up the pressure. We tell ourselves we just need a holiday. And sometimes that works—for a while. But as soon as we return to the same conditions, the problem resurfaces. Because the issue was never lack of pressure. It was accumulation.

So how do we clean ourselves?

This is where suffering enters the picture.

Suffering is not punishment. It is not moral failure. It is part of a de-clogging program. It interrupts routines. It forces reconfiguration. It dislodges what has settled too comfortably inside us.

If that cleaning fails, replacement follows.

You can think of medicine—think of replacement as healing. But it is not, not yet. Surgical methods are still crude. They cut and remove. They leave scars. Pins. Titanium. A state-of-the-art body repaired by force—well, not repaired but patched. It works for a while, but it is not elegant.

Yes, when I say ‘replacement’ I am talking about the inevitable. Death itself.

Which is why suffering appears earlier in the process.

I am not here to deliver good news. Good news resolves nothing. I am here to push you—to force change.

Do not come to me complaining about your suffering.

Clean your mess and carry on.

That near-death experience.

That accident on the road beside you.

That rejection.

Those were not random events. They were cleaners. You learned from them. Sometimes they unclogged you.

You think I am distant. You imagine me as an image behind glass, a saint in a church, a candle to kneel before. But I am closer than you think. I work through messengers—through events, through interruptions. You only need to observe carefully to realize that I am always guiding you.

Recently, my mother was showing me her photo albums. She pulled out one from my eldest brother’s prom. Poncho. He had syringomyelia, a neurological disease that took his life before he was twenty-five.

He was an accountant. He graduated at nineteen. He knew he had little time, so he rushed. He was brilliant. Even with his condition and his short career, he managed to build an impressive client portfolio.

My mother began telling me about his friends—where they ended up. One became a pastor. Another a successful entrepreneur. Some divorced. Four decades of life unfolding: successes, failures, sorrow, joy.

Poncho did not get that timeline, he has the desire to live, plans, curiosity but his body failed.

I was with him when he died. I remember his last words as if he pronounced them yesterday: “Thanks, you’re a good man”. He said, he was tired and wanted to take a nap. I stayed with him, but I closed my eyes for no more than five minutes. When I woke up, he was gone. I yelled for help crying, but there was nothing left to do.

I don’t feel comfortable speaking about my brother; it’s a subject that still has scars on me and it hurts. But now, caring for my mother, I remember the years when we became his nurses. In his final year we showered him, dressed him, fed him. One system failed after another. Sensation left his fingers. Walking became impossible. Writing stopped. Eventually his diaphragm failed. He could not breathe.

Ten years of watching accumulation turn into collapse.

Parkinson’s follows a similar trajectory. The nervous system degrades slowly. A tic. A tremor. Loss of control. Until one day the heart stops or the lungs fail. The system is clogged.

I cannot stop thinking about how my mother’s path resembles my brother’s—and how little can be done to change that.

In these first days with her, I have noticed patterns. In the morning, she is fine, though the trembling is strongest when she is seated. When she walks, it disappears. In the afternoon she is tired, but the symptoms recede—unless attention is drawn to them. Then pain appears.

One day she taught the nurse how to cook one of her favorite dishes. She stood, walked to the stove, checked the color of the meat. Perfect. No trembling. No pain.

I can imagine how Jorge would react. He would say my brother needed to change his mindset. Clean his environment. Regulate his mood. Drink green potions. Do yoga. Virgin Mary’s letters promise that such small acts preserve function, prevent collapse.

But Poncho did all that. We cleaned his space. We maintained order. We tried to keep his mood stable. We even turned to shamans and witch doctors. And still, one system after another shut down.

The maintenance protocols failed.

So when I watch my mother at the stove—steady, smiling, momentarily free of tremor—I want to believe Jorge is right. That mood preserves function. That cleaning prevents collapse.

But I also know what I know: sometimes the breakers flip regardless. Sometimes accumulation wins.

The question is not whether Virgin Mary’s letters work.

The question is: for how long? under which circumstances?

Mood affects health. There is no doubt. Maybe these letters are just buying time.

This is not about perfection. It is not even about healing.

Jorge may have slowed his Parkinson’s. My brother could not. My mother will not.

But watching her stand at the stove, checking the color of the meat—maybe that is what the letters are actually offering. Not a cure. Not prevention. Just moments. Brief windows where the system flows clearly before the next accumulation begins.

Small acts that buy time.

That preserve dignity.

That make you feel you are here, now.

That create pockets of function within inevitable decline.

I know it is not salvation. There are limits, I understand.

It is not about the future or the past. It is about today. About attention.

Your thoughts matter—that seems to be the mantra.

Leave a comment